Fabulosity III

by

Bronwyn Mills

|

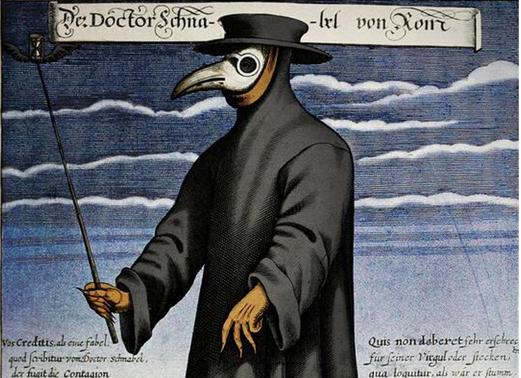

The Paris Review monthly column, "Happily," sports a bland, if not sappy, billing: "focuses on fairy tales and motherhood." That lead suspiciously reads as if written by one who considers nothing worthy but the "realism" of the dull grey Anglo bourgeoisie. Normally, that that alone would provoke me to happily turn the page. Yawn––cloying domesticity! But Sabrina Orin Mark’s April 6th column, "The Fairy Tale Virus" caught my eye. First, as here, is its graphic reproduction of Paulus Fürst’s stunning Plague Doctor, created around 1656, a not altogether unfamiliar figure invoked in these troubled times. For we have all heard the comparisons, Corona virus likened to the plague, or plagues, that decimated so many in the Middle Ages.

|

Orin Marks begins her monthly with the traditional folktale segue, "Once upon a time…" personifying the agent of our contemporary crisis:

Once upon a time a Virus With A Crown On Its Head swept across the land. An invisible reign. A new

government. "Go into your homes," said the Virus, "or I will eat your lungs for my breakfast, lunch, and

dinner. The city that never sleeps shall fall into a profound slumber, your gold shall turn to dust, and your

face shall be pressed against the windowpane."

Clearly, we are in New York, in the midst of a health as well as a financial crisis, locked away inside. Passover (Easter for Christians). Orin Marks exchanges grim jokes with a friend whose neighbor has been pestering the friend to celebrate with her, rather than observe social distancing: The friend writes, "I’m telling her I’m putting blood on my gate and waiting for death to pass over my house." Of course, spare my first born son––not just that child, but spare me the wider, ominous threat of disinterested, impartially dealt death. This, yes this, Orin Marks insists, this is "the fairy tale I will write about this time." Then, still playing on the several details of our current crisis, hoarding, social disintegration––then, the explanatory whopper:

This is the problem with metaphor and ritual and fairy tales. Sometimes they start leaking into reality, and

no one knows how to sew up the tear. And even if we did know how to sew it up, all the stores are out of

needle and thread.

It is that "tear," the fragile frontier between the real and the imagined is the territory which interests me most. I am of course thinking about the kind of imaginative writing that I have come to categorize under the rubric of the Fabulous, which dares to blur the boundaries between the real, even mundane, and the pyrotechnics of the imagined, the metaphorical, the personified Impossible, and so on. Latin American writers have done it for some time. Kafka did it (I woke up one morning to find myself become a cockroach.) Lewis Carroll did it, despite the façade of writing for a child––the 'real' Alice––and with the knowledge that some of his work could just as well apply to adult life (Take, for example, the apt comparison of Humpty Dumpty and certain lowlife politicians.) Borges did it supremely well: for example, he introduces Uqbar, one of the fabled cities in Ficciones, thus:

"Debo a la conjuncíon de un espejo y de una enciclopedia el descubrimiento de Uqbar." Trans: I owe the

discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror [the former which he further describes as at the end of a

corridor in a home on a street named Gaona] and the latter, as The Anglo-American Cyclopedia (New York

1917) which, in turn "es una reimpresión literal, pero tambien morosa––" is a literal reprint, but also out of

date, of the "Encyclopedia Britannica de 1902."

Are we going to go through the looking glass with the author? Not so fast. Borges then goes on to speak of dining with writer friend, Bioy Cesares, and discussing a novel written in the first person where the author distorts certain facts–– This is not as an aside but integrated into and part of, Ficciones; all with which Borges casually torments, teases, and enchants us with the easy back and forth, the blurring, of the fantastic and the real.

Ritual is another can of worms. Suffice it to say at this point that, even if we are unbelievers, we inherit much metaphor from a culture infused with certain religious myths and tales. Alternatively, in this funhouse of the fabulous, we suffer from an acute case of repetition compulsion.

In opposition to all this is the unfortunate muzzling, sadly but with some reason credited to the work and teaching of Raymond Chandler at Iowa––some dumbing down of the imaginary in favor of the stultifyingly mundane. Write like you talk. Well, let’s face it, most people do not employ metaphors and personification like Orin Marks does, at least not in conversation. For far too long, MFA programs like Iowa’s have ruthlessly promoted prose that sounds like a perfunctory exchange you might overhear in a restaurant or café, out of the mouths of the worried well, bordering on adolescent, middle class. Or, perhaps, the conversations of the "underclass" as imagined by the insulated bourgeoisie. In either case, in these simulated flights of imagination, the language is polished, albeit bereft of excitement, but the content is like an overcooked fast food meal in a diner somewhere in the Midwest: fried minced meat, grey and laid dead on a styrofoam bun, greasy "fries" slathered with ketchup, i.e. red sugar––Jesus! pass the salt!––coffee so light you can see the bottom of the cup… This is not realism for grownups.

Once upon a time a Virus With A Crown On Its Head swept across the land. An invisible reign. A new

government. "Go into your homes," said the Virus, "or I will eat your lungs for my breakfast, lunch, and

dinner. The city that never sleeps shall fall into a profound slumber, your gold shall turn to dust, and your

face shall be pressed against the windowpane."

Clearly, we are in New York, in the midst of a health as well as a financial crisis, locked away inside. Passover (Easter for Christians). Orin Marks exchanges grim jokes with a friend whose neighbor has been pestering the friend to celebrate with her, rather than observe social distancing: The friend writes, "I’m telling her I’m putting blood on my gate and waiting for death to pass over my house." Of course, spare my first born son––not just that child, but spare me the wider, ominous threat of disinterested, impartially dealt death. This, yes this, Orin Marks insists, this is "the fairy tale I will write about this time." Then, still playing on the several details of our current crisis, hoarding, social disintegration––then, the explanatory whopper:

This is the problem with metaphor and ritual and fairy tales. Sometimes they start leaking into reality, and

no one knows how to sew up the tear. And even if we did know how to sew it up, all the stores are out of

needle and thread.

It is that "tear," the fragile frontier between the real and the imagined is the territory which interests me most. I am of course thinking about the kind of imaginative writing that I have come to categorize under the rubric of the Fabulous, which dares to blur the boundaries between the real, even mundane, and the pyrotechnics of the imagined, the metaphorical, the personified Impossible, and so on. Latin American writers have done it for some time. Kafka did it (I woke up one morning to find myself become a cockroach.) Lewis Carroll did it, despite the façade of writing for a child––the 'real' Alice––and with the knowledge that some of his work could just as well apply to adult life (Take, for example, the apt comparison of Humpty Dumpty and certain lowlife politicians.) Borges did it supremely well: for example, he introduces Uqbar, one of the fabled cities in Ficciones, thus:

"Debo a la conjuncíon de un espejo y de una enciclopedia el descubrimiento de Uqbar." Trans: I owe the

discovery of Uqbar to the conjunction of a mirror [the former which he further describes as at the end of a

corridor in a home on a street named Gaona] and the latter, as The Anglo-American Cyclopedia (New York

1917) which, in turn "es una reimpresión literal, pero tambien morosa––" is a literal reprint, but also out of

date, of the "Encyclopedia Britannica de 1902."

Are we going to go through the looking glass with the author? Not so fast. Borges then goes on to speak of dining with writer friend, Bioy Cesares, and discussing a novel written in the first person where the author distorts certain facts–– This is not as an aside but integrated into and part of, Ficciones; all with which Borges casually torments, teases, and enchants us with the easy back and forth, the blurring, of the fantastic and the real.

Ritual is another can of worms. Suffice it to say at this point that, even if we are unbelievers, we inherit much metaphor from a culture infused with certain religious myths and tales. Alternatively, in this funhouse of the fabulous, we suffer from an acute case of repetition compulsion.

In opposition to all this is the unfortunate muzzling, sadly but with some reason credited to the work and teaching of Raymond Chandler at Iowa––some dumbing down of the imaginary in favor of the stultifyingly mundane. Write like you talk. Well, let’s face it, most people do not employ metaphors and personification like Orin Marks does, at least not in conversation. For far too long, MFA programs like Iowa’s have ruthlessly promoted prose that sounds like a perfunctory exchange you might overhear in a restaurant or café, out of the mouths of the worried well, bordering on adolescent, middle class. Or, perhaps, the conversations of the "underclass" as imagined by the insulated bourgeoisie. In either case, in these simulated flights of imagination, the language is polished, albeit bereft of excitement, but the content is like an overcooked fast food meal in a diner somewhere in the Midwest: fried minced meat, grey and laid dead on a styrofoam bun, greasy "fries" slathered with ketchup, i.e. red sugar––Jesus! pass the salt!––coffee so light you can see the bottom of the cup… This is not realism for grownups.

* * *

Now, in my first ruminations on the subject of fabulosity, "Flights of the Fabulous" Issue #8 (and featured there as a colophon,) I mused about the wobbly relationships we human beings have had and still have with the natural world. I quote myself:

Domesticity, the wild, the need to make sense of the miraculous and evade harm…the

creation of stories, sacred and profane, that are both talismans against the fearful unknown,

the uncontrollable…

What is at odds is the tame and untamed, the raw, if you will, and the cooked. The act of "making sense," in traditional societies without objective, observational analysis often meant ascribing magical powers to natural phenomenon, whether that magic was accomplished by spirits, a god or gods, or simply rested in the creature so ascribed.

As Orin Marks points out, our 21st century plague, the "Virus With A Crown On Its Head," fantasy has leaked out into reality, if nothing else, in the metaphors and the footnoted comments we are now resorting to in an effort to contain our fear. Fear? Fear, this time, of illness and death, yes, of course; but perhaps even more, our fear of nature itself. For the virus is not, as some nutter conspiracy theorists would have, something concocted in a lab to subvert our polity––no, no, it is a biological entity, part and parcel of what our predecessors once called the Great Chain of Being.

In times past, religion used to be more of a protective cloak. However, religious ideology sometimes—often, in the case of monotheisms—set limits on a genuine flight of imagination; sadly, it ascribed a humanly-conceived "magic" to the natural world but simultaneously missed the inherent wonder in it. More fear of, than wonder; more domination of, than working with/within. Indeed, in Middle Ages Europe, the natural world was out of human control, full of real and imagined dangers, demons, fairies, unpredictable attacks by the real and the unreal. Without science, behaviors within that world were explained by bizarre, superstitious "theories," fantastical tales, with, only on the rarest occasion, some attempt at observation-based accounting.

However, if true to itself, while the fabulist story can portray the invented and the miraculous, it must escape the bonds of superstition’s ideology, on the one hand, and the ideology of social realism on the other. So-called "fairy tales," the generic term for "unrealism," imaginative telling, says Orin Marks, must infect us must attach, enter, replicate, biosynthesize, assemble, and release. Fairy tales, like a virus that blooms into a global pandemic, cross borders and enter us. The storyteller is the infector. The storyteller retells their body’s story in the body of another.

Yes, such telling must do more than entertain us; it must seize us. One does not achieve that kind of effect by sterilizing the imagination, drowning out the terror of knowing that we, too, are as subject to the laws of nature––including death––as any other mammal, any virus, rather than the center of a cramped and narcissistic universe. The Fabulous may intrigue us, enchant, and delight, but it has a darker, or should I say deeper, side; and it should not be confused with the well-crafted, soothing words of realism’s self-serving lullabies.

Thus, in my second essay on the subject, "Fabulosity," I mused on the nature of tales and fables and their impact upon our psyche as expounded by writers exploring that subject non-fictionally. In short, thoughts on the tales’ darker side as expounded by Bettelheim, Tolkien, even G.K.Chesterton. They speak of the magic in those tales as "rescuing" a child from a sense of threat or situation of danger. But I also noted two, in my mind, rather distressing phenomenon: "Other than the psychic advantages of the fairy tale as Bettelheim and others have justly claimed, however, magic as a solution, a strategy, is not for grownups." Thus, if a tale is too fabulous––whatever "too fabulous" might mean––relegate it to the children’s room; and, secondly, if you catch someone telling these tales, do not trust them. By extension, do not trust the human imagination. And if the purveyor of the imagination is the oddball pathogen that Orin Marks describes, is it any wonder why artists and writers remain the object of persecution by so many dictatorial regimes? from Plato's famous ban on poets in his utopia, The Republic, to the marginalizing of many imaginative writers in favor of literal-minded social realism,

The monster of the fairy tale, so threatening to the child but so easily subdued by that child's imagination,

has become the literalist's monster incarnate—the imagination itself.

Domesticity, the wild, the need to make sense of the miraculous and evade harm…the

creation of stories, sacred and profane, that are both talismans against the fearful unknown,

the uncontrollable…

What is at odds is the tame and untamed, the raw, if you will, and the cooked. The act of "making sense," in traditional societies without objective, observational analysis often meant ascribing magical powers to natural phenomenon, whether that magic was accomplished by spirits, a god or gods, or simply rested in the creature so ascribed.

As Orin Marks points out, our 21st century plague, the "Virus With A Crown On Its Head," fantasy has leaked out into reality, if nothing else, in the metaphors and the footnoted comments we are now resorting to in an effort to contain our fear. Fear? Fear, this time, of illness and death, yes, of course; but perhaps even more, our fear of nature itself. For the virus is not, as some nutter conspiracy theorists would have, something concocted in a lab to subvert our polity––no, no, it is a biological entity, part and parcel of what our predecessors once called the Great Chain of Being.

In times past, religion used to be more of a protective cloak. However, religious ideology sometimes—often, in the case of monotheisms—set limits on a genuine flight of imagination; sadly, it ascribed a humanly-conceived "magic" to the natural world but simultaneously missed the inherent wonder in it. More fear of, than wonder; more domination of, than working with/within. Indeed, in Middle Ages Europe, the natural world was out of human control, full of real and imagined dangers, demons, fairies, unpredictable attacks by the real and the unreal. Without science, behaviors within that world were explained by bizarre, superstitious "theories," fantastical tales, with, only on the rarest occasion, some attempt at observation-based accounting.

However, if true to itself, while the fabulist story can portray the invented and the miraculous, it must escape the bonds of superstition’s ideology, on the one hand, and the ideology of social realism on the other. So-called "fairy tales," the generic term for "unrealism," imaginative telling, says Orin Marks, must infect us must attach, enter, replicate, biosynthesize, assemble, and release. Fairy tales, like a virus that blooms into a global pandemic, cross borders and enter us. The storyteller is the infector. The storyteller retells their body’s story in the body of another.

Yes, such telling must do more than entertain us; it must seize us. One does not achieve that kind of effect by sterilizing the imagination, drowning out the terror of knowing that we, too, are as subject to the laws of nature––including death––as any other mammal, any virus, rather than the center of a cramped and narcissistic universe. The Fabulous may intrigue us, enchant, and delight, but it has a darker, or should I say deeper, side; and it should not be confused with the well-crafted, soothing words of realism’s self-serving lullabies.

Thus, in my second essay on the subject, "Fabulosity," I mused on the nature of tales and fables and their impact upon our psyche as expounded by writers exploring that subject non-fictionally. In short, thoughts on the tales’ darker side as expounded by Bettelheim, Tolkien, even G.K.Chesterton. They speak of the magic in those tales as "rescuing" a child from a sense of threat or situation of danger. But I also noted two, in my mind, rather distressing phenomenon: "Other than the psychic advantages of the fairy tale as Bettelheim and others have justly claimed, however, magic as a solution, a strategy, is not for grownups." Thus, if a tale is too fabulous––whatever "too fabulous" might mean––relegate it to the children’s room; and, secondly, if you catch someone telling these tales, do not trust them. By extension, do not trust the human imagination. And if the purveyor of the imagination is the oddball pathogen that Orin Marks describes, is it any wonder why artists and writers remain the object of persecution by so many dictatorial regimes? from Plato's famous ban on poets in his utopia, The Republic, to the marginalizing of many imaginative writers in favor of literal-minded social realism,

The monster of the fairy tale, so threatening to the child but so easily subdued by that child's imagination,

has become the literalist's monster incarnate—the imagination itself.

|

To distinguish further between superstition and imagination: to put it simply, the former confines us with the shackles of fear; the fear of change, of those not like us, fear of the theft of our illusion of "freedom" as a synonym for "convenience," self-indulgence. It enables obedience to authority, no matter how arbitrary.

Imagination frees us through creativity—for a time. It does not promise eternal life. We and our tales are finite, both a comfort and a terror, freeing the psyche, yes, but also the spirit. To be continued… For the two earlier essays on the subject, as noted see "Flights of the Fabulous" Issue #8 (featured there as a colophon.) and "Fabulosity," Issue #9 Further ruminations may appear as this author is so moved. |