|

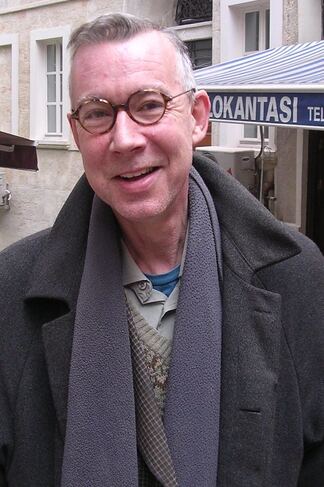

JOHN ASH

(June 1948 - December 2019) |

Early evening, the phone in my Beyoğlu apartment rang. It was Ash: "Hello, John." "Hello, Bron-wen. I've just written a po-em," he enunciated in his mellifluous British accent, "Would you like to hear it?" "Yes. Yes, of course." We both taught at Kadir Has University, housed in an old tobacco factory; and had become friends after he had sold me some of his rugs. Tagging along with one of his "At Your Doorstep" tours for students who were, oddly, not so familiar with the city, I remember his triumph at showing us the oldest library in Istanbul with its rare book of poetry by Suleiman the Magnificent, a book of prophecies from Al Andalus, and other treasures. As we became more friendly, he recommended books on his favourite subject, the Byzantines, and gave me a book which I still treasure, a translation of The Noise of Time, a collection of short stories by Osip Mandelstam. We travelled together, him as freebie travel guide; and I was as anxious to learn as any of his students. He also introduced me to our mutually admired rug dealer, a lovely man (for in those days |

everyone had a rug dealer in Istanbul) and to Layla, a wild and lovely woman who traveled all over the place. Once a teacher, Layla exuded grace and pleasure. Ash was the one who invited me to join our Istanbul English language writers' group; and, while he was often merciless in his critiques of others, I was somehow spared his most withering criticisms. After reading several sections of the novel I was working on at the time, he once commented, "Well, Bron-wen, you've become a novelist." How I treasured that praise!

I remember meeting him, sometimes alone and sometimes with others, for after-work drinks at the Buyuk Londres hotel near Istiklal, the main shopping promenade in Beyoğlu. It was John who first introduced me to the place, a Kemalist establishment with pictures of Atatürk on all the walls, and a collection of old ceramic stoves ubiquitously displayed.

That first time, he sat me down near a window. Someone coughed behind me and I turned around. But there was nothing but the drawn curtains and that window.

John snickered. "That's the parrot—"

"Parrot?"

"Yes., there's a parrot behind the curtains. The parrot has learned to imitate a smoker's cough." John lit up a cigarette, "The parrot also does car alarms, a few odd songs in Turkish..."

I remember his concern for the street children of Istanbul. These children, who were often sent by their parents from the East to Istanbul to survive on their own, and, at best, perhaps to send some money home—a number of them turned to sniffing glue. You would see them with a paper bag scrunched at one end held to their faces, inhaling the fumes which would get them high and destroy their brains in a matter of a only a very few years. There was one boy who would beg near John's house—"So far, no glue sniffing, thank god!" John would remark, as he helped the boy with some change. "I'd take him in, but then everyone would think I was a pederast. Imagine! Who would want to have sex with a child?"

Sadly, I also remember friend Mel and I helping a drunk and stumbling John home after the opening of a new restaurant, situated along one of the winding streets in the meyhane district behind Istiklal where people sat out in little cordoned-off areas to drink wine or rakı and share meses, the Turkish equivalent of tapas: He is so thin, I thought, shocked, as Mel and I tried to guide him along by putting our arms around his waist.

One of the more memorable trips we took together was to Afyon,, in 2014. We walked along the streets of Afyon and under the overhanging verandas that traditionally allowed women to look out on the street, to get some air I supposed, while being confined to the house. From there we traveled to visit the Phrygian tombs dedicated to an ancient Mother Goddess, and then on to Lake Eğirdir and out onto a narrow spit of land to the breakwater island, Yeşilada. "Well," John announced after a busy day of sightseeing and after we had booked our respective rooms in a hotel on the island, "I'm going to go down an have a nice, refreshing glass of rakı—join me?" I remember thinking—A nice glass? I knew it would be many nice glasses.

"Thanks, I'll have glass of wine and then I want to go back to my room and do some writing."

"Of course."

And I did.

The next day we spent much time questioning folks thither and you about Prostanna, a city of "wild Pisidians," as John later put it in "Looking for Prostanna," a poem about our search which, till I saw it in print, I did not know had been dedicated to me. The afternoon in question we had rented a cab and went chasing up the side of a dauntingly precipitous mountain looking for the ruins. Alas, my old fear of heights thrust itself in my face: "Bronwyn winced, and moaned in the back seat,/Head down, and I said, perhaps a little callousely:/Well, dear, you wanted to see the Taurus Mountains..." Despite finally arriving at a sign, "Prostanna" (presumably the ruins mentioned in classical Greek writing as early as in 113 B.C.) we also arrived at the end of the road, and did not find anything:

I remember meeting him, sometimes alone and sometimes with others, for after-work drinks at the Buyuk Londres hotel near Istiklal, the main shopping promenade in Beyoğlu. It was John who first introduced me to the place, a Kemalist establishment with pictures of Atatürk on all the walls, and a collection of old ceramic stoves ubiquitously displayed.

That first time, he sat me down near a window. Someone coughed behind me and I turned around. But there was nothing but the drawn curtains and that window.

John snickered. "That's the parrot—"

"Parrot?"

"Yes., there's a parrot behind the curtains. The parrot has learned to imitate a smoker's cough." John lit up a cigarette, "The parrot also does car alarms, a few odd songs in Turkish..."

I remember his concern for the street children of Istanbul. These children, who were often sent by their parents from the East to Istanbul to survive on their own, and, at best, perhaps to send some money home—a number of them turned to sniffing glue. You would see them with a paper bag scrunched at one end held to their faces, inhaling the fumes which would get them high and destroy their brains in a matter of a only a very few years. There was one boy who would beg near John's house—"So far, no glue sniffing, thank god!" John would remark, as he helped the boy with some change. "I'd take him in, but then everyone would think I was a pederast. Imagine! Who would want to have sex with a child?"

Sadly, I also remember friend Mel and I helping a drunk and stumbling John home after the opening of a new restaurant, situated along one of the winding streets in the meyhane district behind Istiklal where people sat out in little cordoned-off areas to drink wine or rakı and share meses, the Turkish equivalent of tapas: He is so thin, I thought, shocked, as Mel and I tried to guide him along by putting our arms around his waist.

One of the more memorable trips we took together was to Afyon,, in 2014. We walked along the streets of Afyon and under the overhanging verandas that traditionally allowed women to look out on the street, to get some air I supposed, while being confined to the house. From there we traveled to visit the Phrygian tombs dedicated to an ancient Mother Goddess, and then on to Lake Eğirdir and out onto a narrow spit of land to the breakwater island, Yeşilada. "Well," John announced after a busy day of sightseeing and after we had booked our respective rooms in a hotel on the island, "I'm going to go down an have a nice, refreshing glass of rakı—join me?" I remember thinking—A nice glass? I knew it would be many nice glasses.

"Thanks, I'll have glass of wine and then I want to go back to my room and do some writing."

"Of course."

And I did.

The next day we spent much time questioning folks thither and you about Prostanna, a city of "wild Pisidians," as John later put it in "Looking for Prostanna," a poem about our search which, till I saw it in print, I did not know had been dedicated to me. The afternoon in question we had rented a cab and went chasing up the side of a dauntingly precipitous mountain looking for the ruins. Alas, my old fear of heights thrust itself in my face: "Bronwyn winced, and moaned in the back seat,/Head down, and I said, perhaps a little callousely:/Well, dear, you wanted to see the Taurus Mountains..." Despite finally arriving at a sign, "Prostanna" (presumably the ruins mentioned in classical Greek writing as early as in 113 B.C.) we also arrived at the end of the road, and did not find anything:

Afyon, Turkey.

Photo: Bronwyn Mills

"We turned back, conscious of an exceptional failure./The city was too far. We had been misled. But I/Did not excuse myself. Prostanna remained an idea,/Something like a thornbush or a cloud, blocking us."

John and I semi-fell out over the last trip we planned when I mentioned that an Israeli friend had invited me to visit him in Israel, and that I would arrive in Istanbul just after that sortie. John defined himself as "Labour, Labour, Labour" and was, like many, in sympathy with the Palestinians. (In fact so was my friend, as was I; but I did not get a chance to tell him that.) After I had left Istanbul, sans the trip with John, I heard that his family had brought him back from Turkey, quite ill. "Alcoholic dementia" was one term that kept coming back...

On my last visit to England, a mutual friend there asked if I was going to see John. "I would, though I'm not sure he would remember me." I replied. Or welcome my presence, I thought.

On December 3rd, John died. When one loses a peer, a friend like that, we selfishly feel

it as a loss of a whole chunk of our own life. True; subsequent events had separated us, but I still felt his absence— "Something like a thornbush or a cloud..."

John and I semi-fell out over the last trip we planned when I mentioned that an Israeli friend had invited me to visit him in Israel, and that I would arrive in Istanbul just after that sortie. John defined himself as "Labour, Labour, Labour" and was, like many, in sympathy with the Palestinians. (In fact so was my friend, as was I; but I did not get a chance to tell him that.) After I had left Istanbul, sans the trip with John, I heard that his family had brought him back from Turkey, quite ill. "Alcoholic dementia" was one term that kept coming back...

On my last visit to England, a mutual friend there asked if I was going to see John. "I would, though I'm not sure he would remember me." I replied. Or welcome my presence, I thought.

On December 3rd, John died. When one loses a peer, a friend like that, we selfishly feel

it as a loss of a whole chunk of our own life. True; subsequent events had separated us, but I still felt his absence— "Something like a thornbush or a cloud..."