For survival, for sanity, and for, yes, some very selfish reasons, we construct the world in which we exist in certain, ways. Specifically, I mean we “construct” truths about and around the people whom we let in—or must accept—our parents, teachers, bosses, siblings, friends… When we lose our parents, a certain set of emotional assumptions about the world goes with them: you are on your own now, gone is that one who has offered you a shoulder to cry on, given you advice, given you disapproving looks at the dinner table. I have no siblings, so I cannot imagine that loss; but the loss of close friends has sparked everything from anger (how could you kill yourself?) to flat out grief. Alternatively, the very thought of the loss of a child is unbearable, and I do not wish that on anyone.

When my own father died, early, the loss also meant the loss of a place, a home, a country life; for we lived on a farm, and my mother moved us into a small college town. I felt very much alone there. When my friend, John Ash, died, he took a part of my life in Istanbul with him. Once more, you feel that sense of aloneness, loss of person, relationship, a place or a home or way of being which had just seemed part of life, part of, to use a hackneyed phrase, who you are. Chapter X or Y has ended.

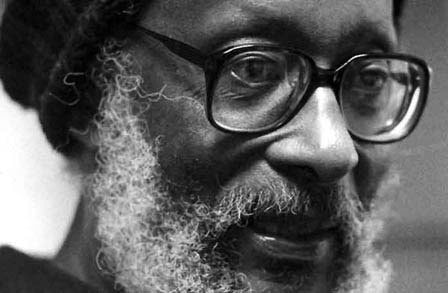

Now Kamau Brathwaite, a mentor (we liked to joke when I was his graduate assistant, a tormentor,) a teacher who pried open my mind, encouraged creativity, a faraway friend (he being in New York, then Barbados, while I galivanted around the world…). I remember those years in New York as ones of incredible intellectual and creative stimulus. In the long run, although I left academia, Kamau stayed in touch—erratically, kindly and genuinely. Selfishly, since his death this February 4th, yes I do feel as though a significant part of my world has crumbled. More importantly, the larger world has also lost his voice and is smaller for it.

“Brrron-WEN—” it was Kamau on the phone, asking me for directions to an event he had been invited to attend. Only he could pronounce my name with its original Welsh burr.

“You take the A train, change at Columbus Circle…”

“Never mind. Come with me. You can show me the way.” It was often thus. I met a lot of interesting people that way—Edwidge Danticat, Gordon Rohlehr, Gayatri Spivak (not my fave), Amiri Baraka (well, would have; he didn’t show up though we waited for some time in an offbeat café in the East Village), the similarly evasive George Lamming (now the last man standing of Kamau’s generation of Anglophone Caribbean writers) and more.

I was his graduate assistant, and my duties included everything from keeping track of his classes and students to helping him negotiate the New York City subway system to getting him to events on time. “I never learned how to take care of myself,” he once confessed out of thin air, and began to reminisce about his days in his native Barbados when he could not help but stand out as special and when his mother made sure she cared for this bright young boy as one would a hot house plant. Ultimately he became, in his words “a scholarship boy,” which in Bajan parlance meant a bright student from the colonies who went to the Metropole (in this case Cambridge) to study.

At the same time, I have a vivid memory of walking by his side, crossing Washington Square Park from school and listening to him bemoan the current crop of graduate students whose class he had just finished teaching—“Why don’t they want to understand?”

“They’re afraid, Kamau. You are taking them into unfamiliar territory; and all they know is the straight and narrow, the criticism, the “theory” they think they must parrot.”

I remembered my own classes with him. He began innocently enough, reading from his The Arrivants, introducing the subject of European colonization in the Caribbean:

When my own father died, early, the loss also meant the loss of a place, a home, a country life; for we lived on a farm, and my mother moved us into a small college town. I felt very much alone there. When my friend, John Ash, died, he took a part of my life in Istanbul with him. Once more, you feel that sense of aloneness, loss of person, relationship, a place or a home or way of being which had just seemed part of life, part of, to use a hackneyed phrase, who you are. Chapter X or Y has ended.

Now Kamau Brathwaite, a mentor (we liked to joke when I was his graduate assistant, a tormentor,) a teacher who pried open my mind, encouraged creativity, a faraway friend (he being in New York, then Barbados, while I galivanted around the world…). I remember those years in New York as ones of incredible intellectual and creative stimulus. In the long run, although I left academia, Kamau stayed in touch—erratically, kindly and genuinely. Selfishly, since his death this February 4th, yes I do feel as though a significant part of my world has crumbled. More importantly, the larger world has also lost his voice and is smaller for it.

“Brrron-WEN—” it was Kamau on the phone, asking me for directions to an event he had been invited to attend. Only he could pronounce my name with its original Welsh burr.

“You take the A train, change at Columbus Circle…”

“Never mind. Come with me. You can show me the way.” It was often thus. I met a lot of interesting people that way—Edwidge Danticat, Gordon Rohlehr, Gayatri Spivak (not my fave), Amiri Baraka (well, would have; he didn’t show up though we waited for some time in an offbeat café in the East Village), the similarly evasive George Lamming (now the last man standing of Kamau’s generation of Anglophone Caribbean writers) and more.

I was his graduate assistant, and my duties included everything from keeping track of his classes and students to helping him negotiate the New York City subway system to getting him to events on time. “I never learned how to take care of myself,” he once confessed out of thin air, and began to reminisce about his days in his native Barbados when he could not help but stand out as special and when his mother made sure she cared for this bright young boy as one would a hot house plant. Ultimately he became, in his words “a scholarship boy,” which in Bajan parlance meant a bright student from the colonies who went to the Metropole (in this case Cambridge) to study.

At the same time, I have a vivid memory of walking by his side, crossing Washington Square Park from school and listening to him bemoan the current crop of graduate students whose class he had just finished teaching—“Why don’t they want to understand?”

“They’re afraid, Kamau. You are taking them into unfamiliar territory; and all they know is the straight and narrow, the criticism, the “theory” they think they must parrot.”

I remembered my own classes with him. He began innocently enough, reading from his The Arrivants, introducing the subject of European colonization in the Caribbean:

|

Parrots screamed. Soon he would touch

our land, his charted mind’s desire. The blue sky blessed the morning with its fire. But did his vision fashion, as he watched the shore, the slaughter that his soldiers furthered here? Pike point and musket butt, hot splintered courage, bones cracked with bullet shot, tipped black book in my belly, the whip’s uncurled desire? Columbus from his after- deck saw bearded fig trees, yellow pouis blazed like pollen and thin waterfalls suspended in the green as his eye climbed towards the highest ridges where our farms were hidden. Now he was sure he heard soft voices mocking in the leaves. What did this journey mean, this new world mean: dis- covery? Or a return to terrors he had sailed from, known before? I watched him pause. Then he was splashing silence. Crabs snapped their claws and scattered as he walked towards out shore. |

and, then

|

3

But now the claws are iron: mouldy dredges do not care what we discover here: the Mississippi mud is sticky: men die there and bouquets of stench lie all night long along the river bank |

—he brought us into the 20th, then 21st, centuries to face the stain of slavery and racism on the land itself. He shocked us with a reading list 100 books long—all on reserve in the library. In yet another class, “Limbo. Limbo like me,” he hummed; then tap, tap; tap, tap, tappity tap as he drummed thumb, forefingers, thumb… on the table in front of him, but not to recall tourists’ clichés, the “dance” under that low bar accompanied by laughter, lots of rum and the lilt of Caribbean English. No. What Kamau was explaining to us, sonically, was the metaphor used by experimental Guyanese novelist Wilson Harris, which was so relevant to all in the Caribbean arts, that forced crouch signifying the abasement and trauma of the Middle Passage.

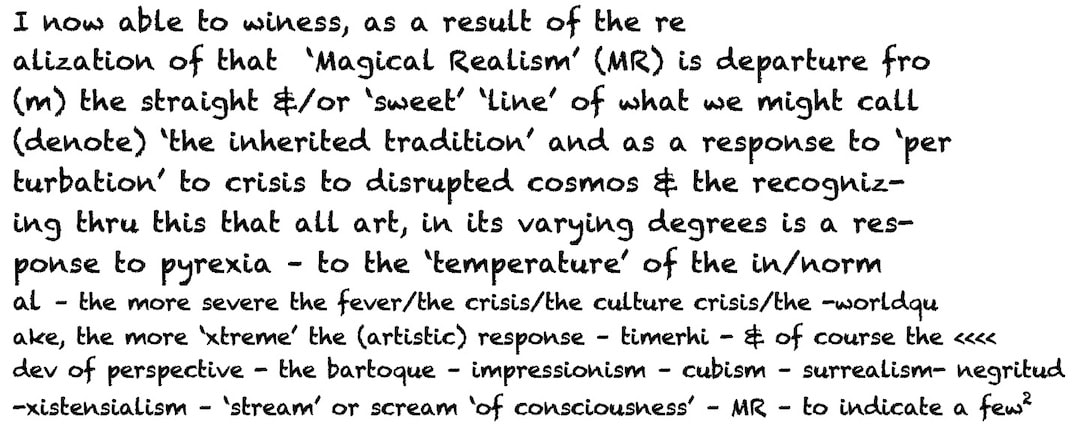

It was Brathwaite’s ongoing struggle to come to terms with an imagination opening itself up to another imagination, to a non-linear discourse that vitally by/sur-passes the step-by-step, ever onwards “logic”—framework, if you will—of European conquerors (the latter culture he quite aptly described/symbolized as “missilic”). He deepened our naïve understanding of James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain and its inherent Shango[1] poetics, the poetics of possession, the buildup of the rhythm of the train, the sonic and very African poetics of Baldwin’s novel. He introduced us to “M.R.”, both the title of his 2-volume series and his acronym for magical realism:

It was Brathwaite’s ongoing struggle to come to terms with an imagination opening itself up to another imagination, to a non-linear discourse that vitally by/sur-passes the step-by-step, ever onwards “logic”—framework, if you will—of European conquerors (the latter culture he quite aptly described/symbolized as “missilic”). He deepened our naïve understanding of James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain and its inherent Shango[1] poetics, the poetics of possession, the buildup of the rhythm of the train, the sonic and very African poetics of Baldwin’s novel. He introduced us to “M.R.”, both the title of his 2-volume series and his acronym for magical realism:

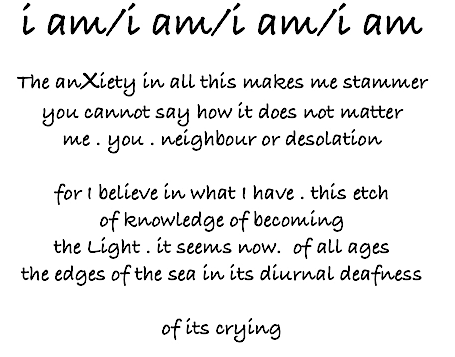

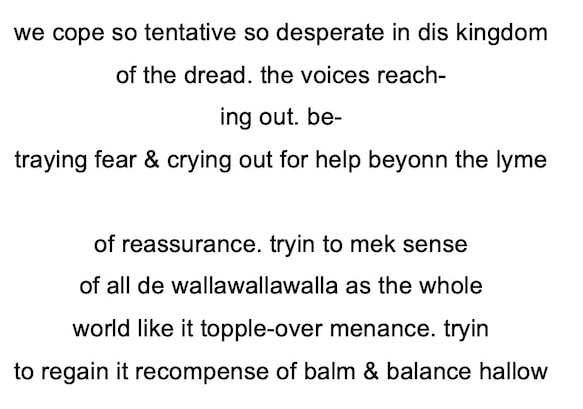

By that time—and more and more—what he called “nation language,” that African possession of his Caribbean language, took center stage, not only in his work, but in his classes, his syllabi, his notes to us. His was a conscious struggle with European sounds and orthography, which he felt unsuited to the precise needs of his creative and intellectual work. More and more, he brought us his view of the legacy embedded in the African consciousness in the Caribbean and, thence, the Americas.

Yes, Kamau taught out of the box. Or, at least, the box academia attempted to confine us in. He rarely used clunky “lit crit speak” in his lectures; he probed, dug deep, suggested what sometimes seemed outlandish ideas—or was it just his own evolving language to come to grips with the African and Caribbean consciousness? And when he was on, he was really on. Shango. The warrior/hunter Ogun. Oshun, Yemanja, Tidelectics[3]…oh, dear, what was that? Were it not for Kamau’s inspired teaching, I would never have even made the fatal decision to focus on Anglophone Caribbean literature in the first place. One day in class, when asked to talk about Jamaican novelist, Erna Brodber, and myal, an African-based religious practice, I produced three objects—a shell, a rock, a sample of a tropical plant—in order to better explain the author’s work. Kamau lit up. Suddenly, in his eyes I became one of his students, not just another academic parrot. No one else would have not only relished but so encouraged my subsequent large collage and watercolor artwork that accompanied the papers he asked us to write by way of intertwined visual explanations for my ideas. Save for Kamau, I would never have been inspired to use his ideas and those of Harris, about how trauma is imbedded in the land itself, as a basis for my dissertation on maps and the Caribbean imagination.

Was it really four years as Kamau’s assistant? Was it more? All told I was at NYU a good decade. I dawdled and dawdled till I was told in no uncertain terms--you have to finish, Bronwyn.

At my defense, Dr. Tim Reiss, Danny Dawson one-time director of the Caribbean Cultural Center and then working at the Natural History Museum, Ngugi wa Thong’o, my other advisor and an ethereal presence on Skype—we all waited, silently hoping Kamau would show up, then heaved a collective sigh of relief when he came, but a few minutes late. For the life of me, I don’t remember what questions he asked, but somehow the dissertation was accepted and I got my PhD. Later, he described me as having whooshed in (when he had, in fact, “whooshed”), “looking formidable in a long mauve dress.” Hardly. I was terrified.

When Kamau gave a reading, his work, his "riddums,” and the music of his poetry made me nearly weep. More than once. And I was by no means the only one. Critics have dissected and discussed his “nation language,” with varying effect, sometimes intellectually aware, incisive, sometimes even—god help us—“objective.” Kamau simply located the language of the African Caribbean where it should be and gave voice to its inherent music. Not a “dialect,” not a mere “accent” or that condescending term, “patois,” the language of the ordinary Caribbean comes out of the speech of many Africans—Yoruba, KiKongo (as per Miss Queenie, a priestess of kumina tradition), Fonbe in Haiti, much more—and not, as Marley so aptly put it, “the King James Ver-sion” or other colonizers’ language equivalents. For all the struggle to put African contributions to the Americas where they properly belong—as a profound and aesthetically central part of its arts—Kamau just did it. What that did for his other students, I can only surmise; for me, it was an understanding that he gave, taking off the blinders the West so patronizingly bestowed and just looking at the world of Caribbean and African creativity straight in the face, as is. No excuses.

He was firm about how he wanted his own work to appear, whether it was simply a matter of how the language should unfold, his particular spelling, or the use of his “video style,” Sycorax-ian computer fonts that, he insisted, must be reproduced by the publishers as integral to the work. If they didn’t agree, he just went on and published them himself via Savacou North, his own imprint. (The M.R. quotation above is an attempt to replicate his video fonts.) M.R., mistakenly spelled “Mr” by Goodreads, was one of those—a two volume discourse, visually and verbally brilliant, which completely dispenses with the false image of Grandma’s-overly-domesticated-ghost-speaking-to-us-cozily or any other “cutesy” rendition of that style, so misunderstood in North America, known as “magical realism.” I had the privilege, as his student and as his assistant, of sitting in twice on his class on the subject. He understood that form as an artistic reaction to the collective trauma of the European “civilizing” mission, its assault on the Caribbean and the Americas; he understood that, enchanted though a reader might be, the work was deadly serious.

Even after I went on to other things, we always kept in touch, though “touch” was, as I wrote to one of the others who knew him (and as they, too, experienced),

Yes, Kamau taught out of the box. Or, at least, the box academia attempted to confine us in. He rarely used clunky “lit crit speak” in his lectures; he probed, dug deep, suggested what sometimes seemed outlandish ideas—or was it just his own evolving language to come to grips with the African and Caribbean consciousness? And when he was on, he was really on. Shango. The warrior/hunter Ogun. Oshun, Yemanja, Tidelectics[3]…oh, dear, what was that? Were it not for Kamau’s inspired teaching, I would never have even made the fatal decision to focus on Anglophone Caribbean literature in the first place. One day in class, when asked to talk about Jamaican novelist, Erna Brodber, and myal, an African-based religious practice, I produced three objects—a shell, a rock, a sample of a tropical plant—in order to better explain the author’s work. Kamau lit up. Suddenly, in his eyes I became one of his students, not just another academic parrot. No one else would have not only relished but so encouraged my subsequent large collage and watercolor artwork that accompanied the papers he asked us to write by way of intertwined visual explanations for my ideas. Save for Kamau, I would never have been inspired to use his ideas and those of Harris, about how trauma is imbedded in the land itself, as a basis for my dissertation on maps and the Caribbean imagination.

Was it really four years as Kamau’s assistant? Was it more? All told I was at NYU a good decade. I dawdled and dawdled till I was told in no uncertain terms--you have to finish, Bronwyn.

At my defense, Dr. Tim Reiss, Danny Dawson one-time director of the Caribbean Cultural Center and then working at the Natural History Museum, Ngugi wa Thong’o, my other advisor and an ethereal presence on Skype—we all waited, silently hoping Kamau would show up, then heaved a collective sigh of relief when he came, but a few minutes late. For the life of me, I don’t remember what questions he asked, but somehow the dissertation was accepted and I got my PhD. Later, he described me as having whooshed in (when he had, in fact, “whooshed”), “looking formidable in a long mauve dress.” Hardly. I was terrified.

When Kamau gave a reading, his work, his "riddums,” and the music of his poetry made me nearly weep. More than once. And I was by no means the only one. Critics have dissected and discussed his “nation language,” with varying effect, sometimes intellectually aware, incisive, sometimes even—god help us—“objective.” Kamau simply located the language of the African Caribbean where it should be and gave voice to its inherent music. Not a “dialect,” not a mere “accent” or that condescending term, “patois,” the language of the ordinary Caribbean comes out of the speech of many Africans—Yoruba, KiKongo (as per Miss Queenie, a priestess of kumina tradition), Fonbe in Haiti, much more—and not, as Marley so aptly put it, “the King James Ver-sion” or other colonizers’ language equivalents. For all the struggle to put African contributions to the Americas where they properly belong—as a profound and aesthetically central part of its arts—Kamau just did it. What that did for his other students, I can only surmise; for me, it was an understanding that he gave, taking off the blinders the West so patronizingly bestowed and just looking at the world of Caribbean and African creativity straight in the face, as is. No excuses.

He was firm about how he wanted his own work to appear, whether it was simply a matter of how the language should unfold, his particular spelling, or the use of his “video style,” Sycorax-ian computer fonts that, he insisted, must be reproduced by the publishers as integral to the work. If they didn’t agree, he just went on and published them himself via Savacou North, his own imprint. (The M.R. quotation above is an attempt to replicate his video fonts.) M.R., mistakenly spelled “Mr” by Goodreads, was one of those—a two volume discourse, visually and verbally brilliant, which completely dispenses with the false image of Grandma’s-overly-domesticated-ghost-speaking-to-us-cozily or any other “cutesy” rendition of that style, so misunderstood in North America, known as “magical realism.” I had the privilege, as his student and as his assistant, of sitting in twice on his class on the subject. He understood that form as an artistic reaction to the collective trauma of the European “civilizing” mission, its assault on the Caribbean and the Americas; he understood that, enchanted though a reader might be, the work was deadly serious.

Even after I went on to other things, we always kept in touch, though “touch” was, as I wrote to one of the others who knew him (and as they, too, experienced),

|

… a sporadic but kind correspondence… over the years (last was March of 2018) along with something rather difficult to read in his video style, with some apologies for his failing eyesight, which I remember him complaining about even when I was his grad assistant.

|

Kamau read work I had written in Tupelo Quarterly and Witty Partition (when it was still The Wall); he would send me notes of appreciation or commendation when he found something he liked.

In that last March email, Kamau expressed his usual interest in my doings and his horror at the degradation of US politics, then included a YouTube interview link re: Odale's Choice. I remembered the exchanges between us in the 90s, early 2000s; and then, when I accompanied him to Barbados, that fleeting glance of novelist George Lamming trying to scuttle away from Kamau and the group of students he brought there. Lamming—not to mention the misanthropic Naipaul and other such Anglo-Caribbean writers—these were far more conventional than Kamau in their work, but he made us read them, examine them for their value, and amplify our views. Kamau was also one who consistently gave generous credence to students’ creative side, in the midst of his own struggles with academic conformity and departmental politics. He made his share of enemies, yes; but he never seemed to do rancor very well. He was a gentle, brilliant man. As I wrote to Tim Reiss, who broke the news to me,

In that last March email, Kamau expressed his usual interest in my doings and his horror at the degradation of US politics, then included a YouTube interview link re: Odale's Choice. I remembered the exchanges between us in the 90s, early 2000s; and then, when I accompanied him to Barbados, that fleeting glance of novelist George Lamming trying to scuttle away from Kamau and the group of students he brought there. Lamming—not to mention the misanthropic Naipaul and other such Anglo-Caribbean writers—these were far more conventional than Kamau in their work, but he made us read them, examine them for their value, and amplify our views. Kamau was also one who consistently gave generous credence to students’ creative side, in the midst of his own struggles with academic conformity and departmental politics. He made his share of enemies, yes; but he never seemed to do rancor very well. He was a gentle, brilliant man. As I wrote to Tim Reiss, who broke the news to me,

|

I keep remembering all the odd things about Kamau, slowly filtering through. Of course no one lives forever, but it is still a shock—much more than I imagined it would be. Something about the way, selfishly and from one's perspective, the world is constructed; and then one of the pillars gives way—nothing looks quite the same.

|

After hearing of Kamau’s death, I had nights of dreamed conversations with him: if only--if only, was my first thought upon waking--if only we had talked even more.

***

Towards the end of my days as his student, in class Kamau produced a photograph (this was pre-universal digital photography by cell phone), an eerie black and white photo of a black woman with hollow eyes who, he claimed, had mysteriously appeared to him. In essence, Kamau told us he had stumbled upon a slave burial ground on his property, CowPastor, a dreadful reminder of the period when the wealth of nations was counted in human flesh; and, in the colonizing of the Americas, captive Africans. (The average lifespan of a field slave in those days was 7 years.) In Kamau’s last book of poems, Lazarus, the spirit of Namsetoura, that woman, is one of those hovering over the collection. Tim Reiss, in his considered obituary of Brathwaite has described the poet’s encounter:

|

Namsetoura… emerged from the slave cemetery beneath Cow Pastor, breaking three camera lenses before Kamau could get a vague photo, one eye blazing, one staring, her face ghostly (on the front cover of Born to Slow Horses, her story 118-21, and The Namsetoura Papers, Hambone 17, 2004.) (Reiss 7)

|

Kamau’s account was quite believeable—namely, that the bodies of slaves were tossed away, interred without ceremony or care, as one might throw away a broken tool. Rain Taxi, in a 2005 interview with Kamau, also referenced Kamau’s encounter,

|

a visionary incident in which the specter of an ancestral slave woman, called Namsetoura, appeared to Brathwaite at his home in CowPastor, Barbados [the woman in the photograph.] An angry Namsetoura revealed the spot to be a sacred gravesite and charged Brathwaite not to leave his land, which had been expropriated by the government of Barbados for an airport road.

|

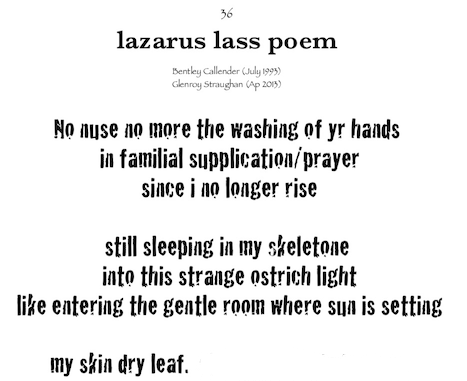

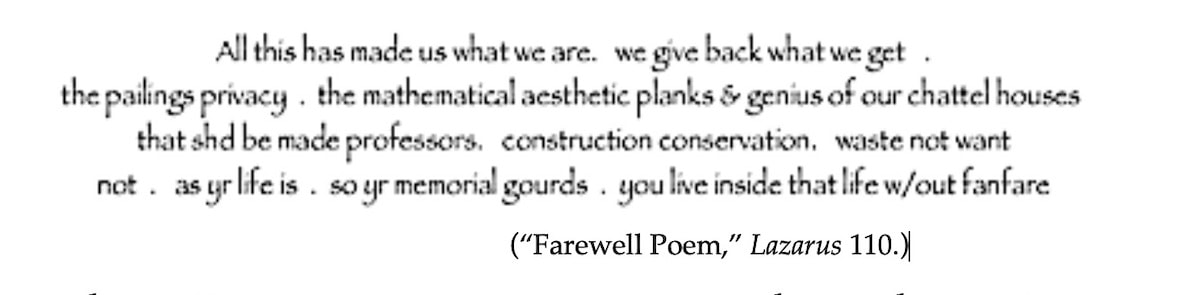

Ten years later, he completed Lazarus, and she is among those mentioned, one needing a proper burial ceremony. Indeed, the first several parts of the work address the rituals of African religions incorporated in the Caribbean’s observances of death, burial, the transiting of that person after kumina and/or myal death journey to reburial, to final separation from this world. Lazarus, the Biblical man whom Jesus raised from the dead, seems in some ways an odd choice for an Afro-Caribbean synecdoche, yet Kamau made it work. I am reminded of that long-ago visit to Barbados and our visit with the Spiritual Baptists (first expression of Christian conversion among enslaved Africans) in Bridgetown: once inside their “church,” I might have sworn we were in an African temple. And the ensuing ceremonies barely disabused us of that fact.

Uncanny, that last work:

Uncanny, that last work:

It speaks of Kamau’s numerous concerns, the centrality of Africa in the Caribbean as he so carefully locates it:

A friend has called attention Louis Armstrong’s phrase, the “dark, sacred night,” so different to the Dylan Thomas invocation to rage, rage, against the dying of the light; Lazarus ends with “Revelation”, a found poem “in the peaceful environment of MR/MR” (115). This stanza could be Kamau, still speaking to us:

April of 2001, Kamau’s wife Beverley tragically lost her son, Mark, aged 29, to an accident (he was sideswiped by a vehicle while on his bicycle in downtown Kingston, Jamaica.) Quite different this grief; but Kamau wrote ”Kumina,” attempting to commemorate a tragic death, assuage Beverly’s sorrow:

As noted, a more considered and detailed obituary by Tim Reiss will appear in the forthcoming

Witty Partition, Issue 10 (April 1, 2020.) Please check back then for Reiss' tribute.

The Poetry Archive has a respectful and brief, though imperfect, obituary with three sound recordings of Kamau reading his work, well worth the listen.

However, the most stunning recordings of several of Kamau’s readings can be found at PennSound.

Awards:

Witty Partition, Issue 10 (April 1, 2020.) Please check back then for Reiss' tribute.

The Poetry Archive has a respectful and brief, though imperfect, obituary with three sound recordings of Kamau reading his work, well worth the listen.

However, the most stunning recordings of several of Kamau’s readings can be found at PennSound.

Awards:

|

Selected Work:

|

[1] West African spirit of thunder, lightning, fire and described by Gordon Rohlehr, Caribbean scholar, as “god of the train,” among his many attributes.

[2] from M.R., 127.

[3] “Tidalectics, said Kamau in 1999, effects a fused geographic, cultural, climatic and political ecology of oceanic tidal motion always rippled by cross-currents, swells, skipping stones....” (Reiss 8) See Tim Reiss’ considered and much more detailed obituary, in Witty Partition, Issue 10.

PLEASE RE-ENJOY WITTY PARTITION ISSUE #10

[2] from M.R., 127.

[3] “Tidalectics, said Kamau in 1999, effects a fused geographic, cultural, climatic and political ecology of oceanic tidal motion always rippled by cross-currents, swells, skipping stones....” (Reiss 8) See Tim Reiss’ considered and much more detailed obituary, in Witty Partition, Issue 10.

PLEASE RE-ENJOY WITTY PARTITION ISSUE #10