Sous le ciel:

Recollections of Notre-Dame de Paris

Eric Darton

|

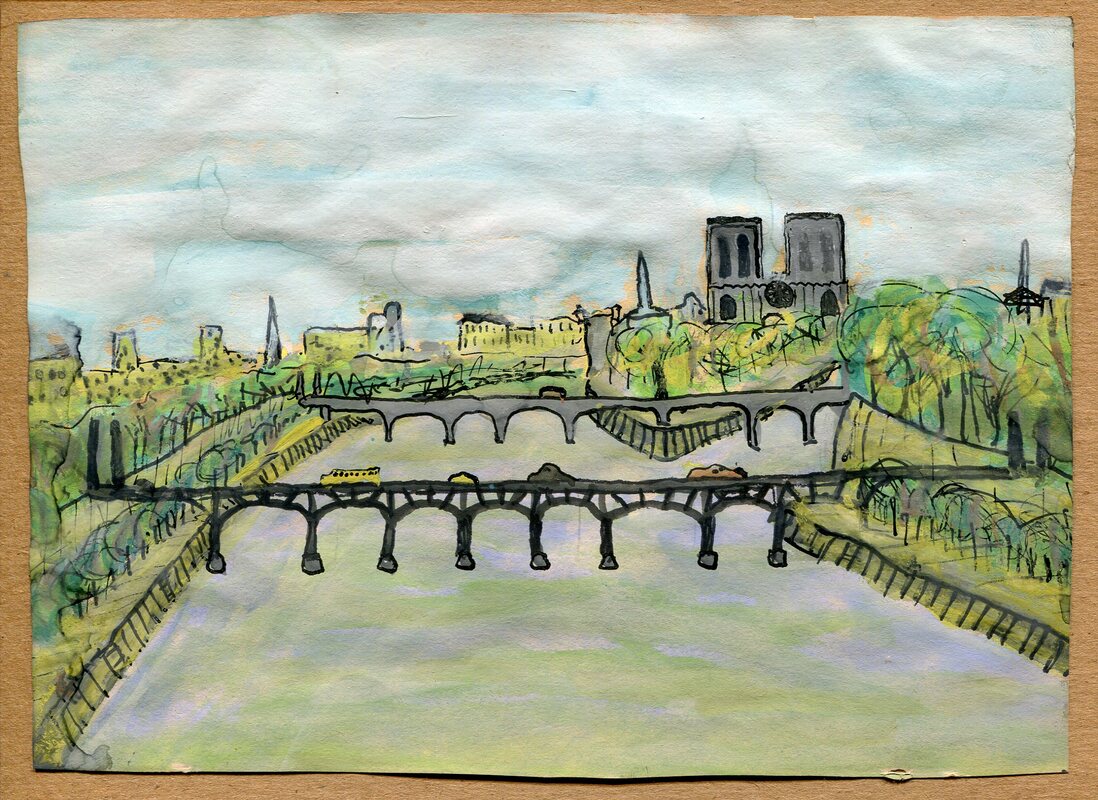

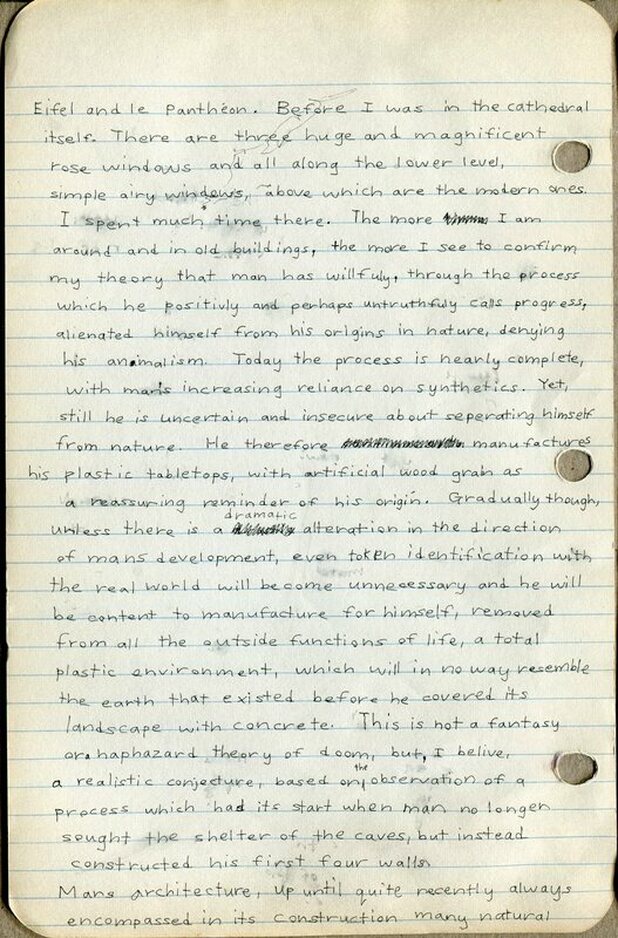

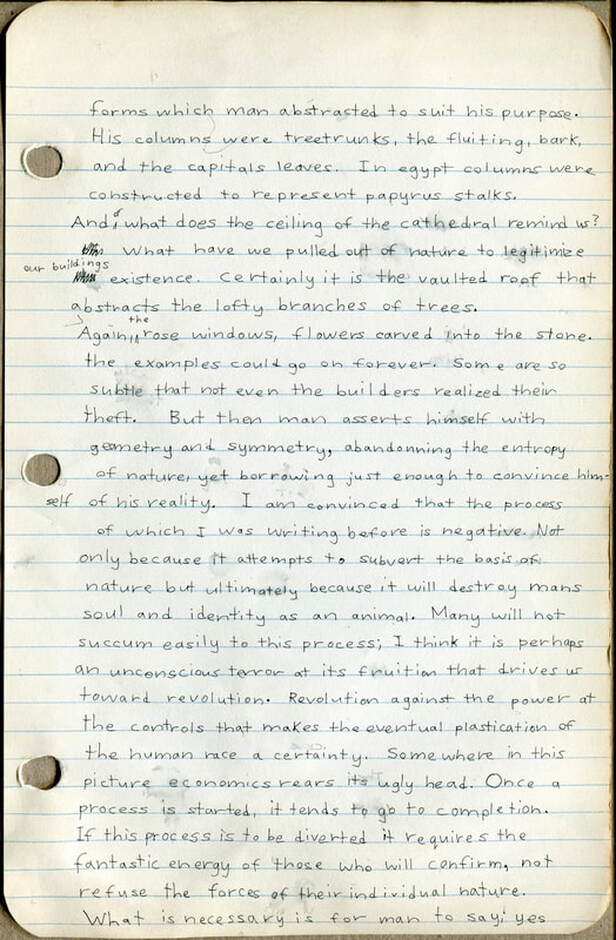

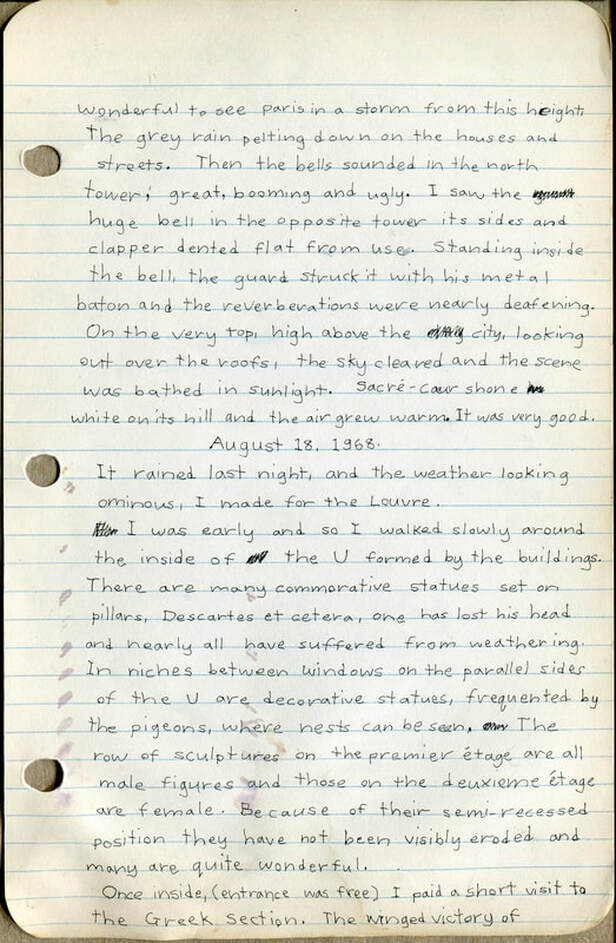

This piece will be a very strange collage. The first fragment dates from 1965 when I was fifteen and visiting Paris with my mother and aunt, on a trip sponsored by the latter. I was given the run of the city while they visited parfumeries, shopped in grands magasins, and sat in cafés, activities in which I then had little interest. Instead I made straight for Notre-Dame. I wanted, among other things, to see where Napoleon had crowned himself emperor. But on passing through the portal and gaining the transept, my historical-political mission was, it is fair to say, obliterated by the sight of the north rose window. It’s also fair to say that although we had a pretty decent fake Tiffany stained-glass lamp over our dining room table, I knew little, until that moment, about the power of transmitted light. I had yet to see the windows in Chartres or Rouen but, Notre-Dame served as a reference point for all that followed. As the song goes: How you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm… Three years later, while my comrades were preparing to riot in Chicago, I took money saved from summer and after school jobs, bought a bike and flew to Europe. My last stop was Paris. Plein été. Hubert Humphrey had yet to become the Democratic Party candidate. RFK was two months dead and George Wallace could still walk. In Paris, many of the streets had newly-paved macadam surfaces, boarded-up shops were being reglazed. Clean-up crews, moving languidly in the late-summer chaleur, sprayed solvent on the ubiquitous graffiti and scrubbed red paint off the Tuilleries statuary. Of course, the most infamous Parisian graffiti of all time had been scrawled seven years earlier and had lasted only a few hours. Its writing, by a person or persons yet unknown, was timed to coincide with a police death-squad massacre of Algerians on October 17, 1961. Parisians crossing Pont Saint-Michel early the next morning saw Ici on noie les Algérians (Here we drown the Algerians) spray-painted on the balustrade. Many bodies, among the approximately three hundred victims, were recovered downstream along the banks of the Seine in subsequent days. The site of the graffiti lay just across the street from the Prefecture of Police building which itself stands in the shadow of Notre-Dame. Soon after arriving in ’68, I visited the cathedral and made a journal entry there. I have reproduced it in facsimile below, preserving both the evidence of raindrops on the paper and ink, along with grammatical and typographical errors. Lo these many years later, I do not have it in my heart to admonish the eighteen-year-old author for his sometimes ill-thought out and over-emphatic notions, nor for his unigendered language which was so ubiquitous at the time as to sound commonplace and seem reasonable. It begins: “August 17, 1968: I am on the south tower of Notre Dame. The river is below. From where I sit I see to my right Sacre-coeur, le consciergerie. Ahead is the Louvre and le Grand Palais. To the left is la tour… |

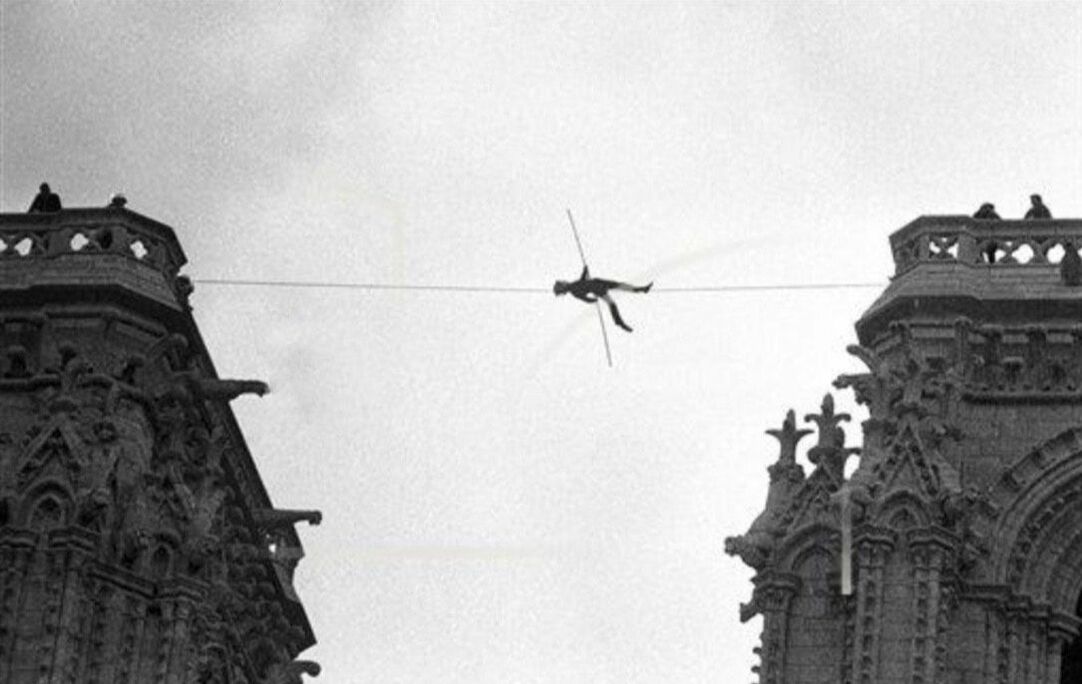

Three years later, Philippe Petit made his transit between the towers.

I would not visit Paris, nor Notre-Dame again until 1986, this time with my wife, Katie.

The author in September, 1986. Photo: Katie Kehrig.

In summer 2001, Katie and I visited Paris with our then-nine year old daughter, Gwen. It was her first time there. Again, I made journal entries:

July 22

Early this morning, Sunday, to the bird market on Île de la Cité near Notre-Dame where Gwen fell under the thrall of a tiny bright orange canary. You convinced her of the logic of not buying it, but nonetheless she named it: Mango.

July 27

Picnic lunch on a bench in the children’s sand park beside the flying buttresses of Notre-Dame. Gwen falls into company with two sisters, Kautar – about her age – and Bouchra, a year or so older. Uncharacteristically flustered, Gwen at first runs back and forth from her playmates to you – “but I don’t speak their language!” – though before long Bouchra shanghaies her into their game. They take turns piling sand into a little hopper, then releasing it to fall through a chute and spin the little wheel below. Soon the three of them arrive at a workable mode of communication: gestures supplemented with rebus shapes drawn in sand, decoded, then swept away. Gwen points to a scarlet patch on her shirt then draws a pencil in the sand, signifying “this is how it is written,” followed by the letters “R - E - D.” And back and forth it goes.

While the girls play, you and Katie exchange pleasantries as best you can with the sisters’ mother and uncle. By the river, in the shadow of the cathedral, as the sand mills round and round, molecules of Casablanca exchange bits of information with molecules of New York. Mother and uncle are here visiting Bouchra and Kautar’s grandfather, who lives in Bobigny. Uncle is a computer technician. When it comes time to go your separate ways, he proudly gave you his email address. You take a picture of the girls standing by the Seine and promise to send a copy.

We returned to Paris, and Notre-Dame, en famille, for five years in succession. This journal entry dates from 2003:

July 2

Hard to imagine that Gwen is due for another birthday soon. For her tenth last year, she saw the Bastille Day fireworks from a terrace on the Tuilleries overlooking Place de la Concorde. Perched on your shoulders. She’s too big to carry that way for long now, and soon she’ll be too cool to want to be lifted up. That’s how it should be if you’ve done your job.

Her nearly-eleven-year-old eyes home in on different things than yours do. You go to the same places, walk the same streets and she notices an altogether different set of signifiers. And what she finds is always grist for her mill. While you browse the Rai music CDs in the giftshop of the Institute du Monde Arabe, she sets about teaching herself French the old fashioned way—by reading the comics. Between the images, idioms and the slapstick humor, Gwen’s hooked—she must have one of the books in the Malika series, even if it costs nearly eight Euros. She offers to pay for it out of her allowance. We’ll see, you say. Have a look for yourself.

Not difficult to spot the protagonist: a shapely, streetwise French-Algerian girl on the cusp of womanhood. With her lower lip set in a perpetual pout and pigtails sticking up like rabbit ears, Malika Secouss (earthquake)—wears outsized black parachute boots and romps with unrestrained joie de vivre through an ongoing comedy of errors set in and around her home turf, La Cité des Pâquerettes (daisies), a bunker-like Corbusian highrise banlieue. Backed up by her motley copains and dogged by her brainy kid sister Zouli, Malika’s an authentic late adolescent—brash, impulsive and deeply clueless. But, like a proper heroine, she triumphs by pluck or luck, and never fails to get the better of the National Front goons and racist flics who hassle her—sometimes by virtue of a well-aimed kick in the groin: GNOK!

There are ten or so books in the series, all written and drawn by Tehem, but this is the particular one Gwen wants. Terrific visual style, lots of vernacular-filled word balloons. Eight Euros. Well, it’s big, full color and hardcover. Sure, why not?

A cloudburst as you walk along the embankment near Notre-Dame, so you take shelter under Pont Neuf. When the rain passes, Katie steps out and starts to sketch the grotesque faces carved into the masonry of the bridge arches. Clever how they’ve hidden the lighting behind panels painted the color of the stonework itself.

You wipe a bench dry and sit with Gwen waiting for Katie to finish. Gwen reads Malika and you quarter a peach. Katie puts away her pad. As you get up you notice you’ve been sitting on some magic-markered graffiti, nearly worn-away by the friction of your jeans and countless other asses. But still visible: Je décrète l’état de bonheur! “I decree the state of happiness.”

As of this writing, in late April, 2019, the two towers, rose windows and a colony of some two hundred thousand bees inhabiting hives on the roof of Notre-Dame survived the blaze.